“Only 10% of non-surgical treatments for back problems kill pain, says review”. This was the title of a recent article in the Guardian, and its main conclusion was that: “Only six out of 56 treatments analysed yielded ‘small’ relief according to the most comprehensive worldwide study, with some even increasing pain” [1].

However, what the Guardian article failed to mention is that the study on which it is based exclusively researched clinical trials that were placebo controlled [2]. In other words, this research made no attempt to cover any of the many hundreds of randomised controlled trials of back pain that compared interventions with other treatments (for example, usual care) instead of with placebo. The study does provide a rationale for reviewing only placebo-controlled trials – it’s simply that we need to understand that the consequence is to ignore any interventions that may have been robustly evaluated by other means. As with any research, the results only apply to what was actually studied, so it would be inaccurate to extend the conclusions to refer to all back pain interventions.

The way that clinical medicine usually works is that when a new disease or condition is identified and a new drug or treatment is developed, the first efficacy trials compare the intervention with placebo. However, once some kind of treatment is available this becomes the usual care until the time when something better comes along. In other words, future clinical trials of new interventions are compared with this usual care to see whether or not they are more efficacious, well tolerated etc, and, if they are, then they will become the standard usual care. This is because for many conditions (think, for example, of a life-threatening illness), it would be unethical to compare a new treatment with placebo because another intervention already exists. Back pain is not (usually) a life-threatening illness and some back pain trials still do use a placebo comparison. However, it is much more common for back pain clinical trials to compare with existing treatments –often this is the usual care provided by a GP.

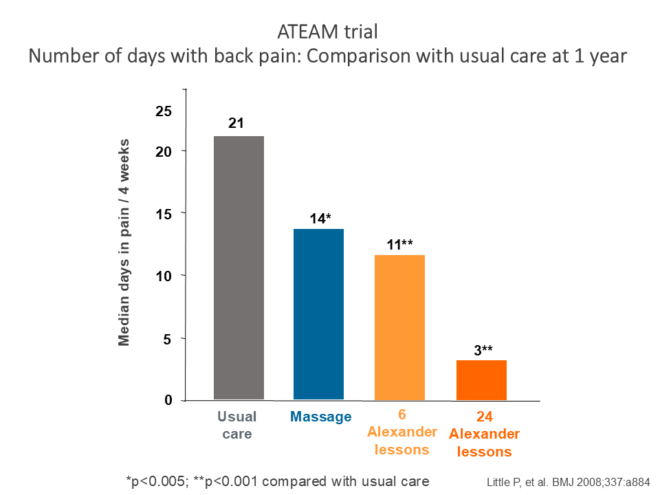

Because the research restricted its remit to placebo-controlled trials, it ignored interventions that have been evaluated against usual care. There are no placebo-controlled trials of the Alexander Technique – it would be extremely difficult to design one (what would a ‘placebo’ Alexander teacher look like?). However, there is a good evidence base for Alexander Technique lessons leading to reduced pain and disability for people living with chronic back pain. Most notably, the ATEAM randomised controlled trial demonstrated that one-to-one Alexander lessons from STAT-registered teachers led to long-term reductions in pain and disability, compared with usual GP-led care [3]. In fact, after one year, the group who had taken 24 Alexander lessons were experiencing only 3 days of pain per month compared with 21 days per month for the group who received usual GP-led care alone (see figure). Also, importantly, the ATEAM trial aimed to allow for any non-specific benefits from touch and attention by including another control group who received massage. While massage was shown to significantly reduce pain, the Alexander lessons were more effective.

Other smaller studies support the conclusions about the effectiveness of Alexander lessons for people with chronic back pain [4–7]. In addition, a second large randomised, controlled trial, called ATLAS, demonstrated that Alexander lessons led to long-term reductions in pain and disability for people with chronic neck pain [8]. This means that two large, robust randomised controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of Alexander lessons in reducing long term pain and disability associated with chronic musculoskeletal conditions.

If we want to understand what research is really telling us, we need to look behind the headlines .

References

[1] Denis Campbell, The Guardian 18 March 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/mar/18/only-10-of-non-surgical-treatments-for-back-problems-kill-pain-says-review.

[2] Cashin AG et al. Analgesic effects of non-surgical and non-interventional treatments for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised trials. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. Published Online First: 18 March 2025. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2024-112974.

[3] Little P; Lewith G; Webley F; et al. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander Technique lessons; exercise and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. British Medical Journal 2008;337:a884.

[4] Little P, Stuart B, Stokes M, Nicholls C, Roberts M, et al. Alexander Technique and supervised physiotherapy exercises in back pain (ASPEN): a four-group randomised feasibility trial. Efficacy Mech Eval 2014;1(2).

[5] Little J, Geraghty AWA, Nicholls C, Little, P. Findings from the development and implementation of a novel course consisting of both group and individual Alexander Technique lessons for low back pain. BMJ Open 2022;12:e039399. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039399.

[6] Vickers AP; Ledwith F; Gibbens AO. The impact of the Alexander Technique on chronic mechanical low back pain (unpublished report). 2000.

[7] Cacciatore TW. Improvement in automatic postural coordination following Alexander Technique lessons in a person with low back pain. Physical Therapy 2005;85:565–78.

[8] MacPherson H, Tilbrook H, Richmond S, Woodman J, Ballard K, Atkin K, Bland M, Eldred J, Essex H, Hewitt C, Hopton A, Keding A, Lansdown H, Parrott S, Torgerson D, Wenham A, Watt I. Alexander Technique lessons or acupuncture sessions for persons with chronic neck pain: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 2015;163:653–62.